By Nina Murray, Research & Policy Coordinator at the European Network on Statelessness.

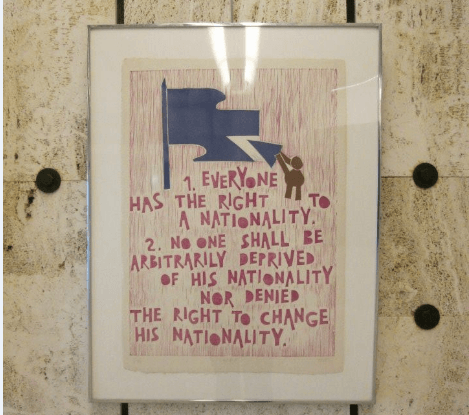

Statelessness is a legal anomaly affecting more than half a million people in Europe – not only recent migrants and refugees, but also people whose families have lived in the same place for generations. For many people, statelessness means denial of the basic rights many of us take for granted: to go to school or work, to get married or register the birth of your child, to ‘legally exist’. All European states have obligations in international law to protect stateless people and prevent statelessness, but in many cases, these have not been translated into effective laws at the national level. More than half a million men, women and children in Europe are falling through these gaps.

And it’s not an issue that is likely to go away any time soon. According to Eurostat, 2.5% of all asylum applicants in the EU in 2016 were stateless or had ‘unknown citizenship. That is around 30,000 people with an identified nationality problem, and the true figure is likely to be much higher given problems with accurate identification at Europe’s borders. At the same time, gender discrimination in nationality laws in many countries of origin, combined with a lack of legal safeguards in European countries to prevent statelessness, mean that some children born to refugees here in Europe are at risk of statelessness. Under Syrian law, for example, women cannot pass on their citizenship to their children, and the UN estimates that a quarter of Syrian refugee households are fatherless.

Organisations supporting refugees and migrants in Europe are increasingly discovering that nationality and statelessness issues are affecting people they work with. Meanwhile, countries across Europe have very different approaches to dealing with statelessness. There is no clear, consistent, or comprehensive approach to identifying who is stateless, granting protection to stateless people, and preventing children from being born stateless in Europe. More clear and comprehensive information and guidance on statelessness in Europe is urgently needed. Stateless people and those working with them need to know who is doing what to respond to the phenomenon, what works, and what their rights are.

The European Network on Statelessness and its members across Europe have developed a new online tool to address this gap. The Statelessness Index enables instant comparison of how different countries protect people without a nationality and what they are doing to prevent and reduce statelessness. It provides extensive country by country analysis of law, policy and practice, which has been benchmarked against international norms and good practice and then assessed using five categories, ranging from the most positive to the most negative. The Index allows users to quickly check law or policy in a specific country, find examples of good practice, and understand where advocacy is most needed to push for reform.

The Index will be an important tool for different audiences. It can support civil society organisations and lawyers helping people affected by nationality problems or advocating with decision-makers for reform; government officials drafting new procedures can look to the Index for examples of good practice from neighbouring countries; students and academics can use it in their research; and stateless people will be able to access important information about their rights and entitlements. As well as checking performance and comparing countries on the main site, users can also download the original country surveys containing all the data, including links and references to national law and policy, which formed the basis of the assessment of a country’s performance. Publishing this data and the sources behind the Index not only helps to ensure transparency, but will also support the work of researchers, lawyers and other experts.

Currently the Index offers comparative data for 12 countries: France, Germany, Macedonia, Malta, Moldova, The Netherlands, Poland, Serbia, Slovenia, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and Ukraine, but we will be adding more countries soon. We will also continue to work with our members and partners to update the country profiles with new information and to develop other useful resources from the Index data, such as policy briefings, training packages, and awareness raising materials.

ECRE publishes op-eds by commentators with relevant experience and expertise in the field who want to contribute to the debate on refugee rights in Europe. The views expressed are those of the author and does not necessarily reflect ECRE positions

This article appeared in the ECRE Weekly Bulletin . You can subscribe to the Weekly Bulletin here.