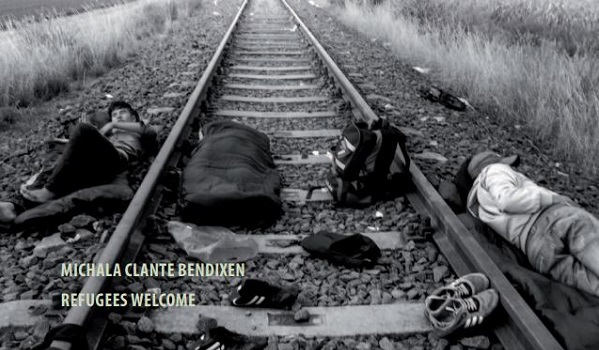

By Michala Clante Bendixen, founder of the Danish organisation Refugees Welcome and the information website REFUGEES.DK.

”Rejected asylum seekers must respect the decision and return home” – it sounds plausible enough to be the political consensus. But a prerequisite for this is of course that the decision of the asylum case was correct to begin with. In Denmark, most rejections are the result of the applicant found not to be credible. I argue that the decisions are not reliable – and that many of the rejected people could therefore be in danger.

As a result of the Danish exceptions to the Maastricht treaty, Denmark is in a particular situation of having an opt-out option in relation to the development of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) as well as potential legislation related to the announced European Pact on Asylum and Migration. However, Denmark is like all other member states bound by central EU and international law and is also under the Dublin regulation.

Yet, beyond the international conventions, human rights principles and rulings from the international courts, each country has its own asylum procedure, its own legislation, and its own practise. At the core of all asylum cases are the ability of the applicants to provide a coherent and detailed account of often extremely traumatic and confusing experiences. In most cases an asylum applicant would have little or no written documentation or personal papers to support them, and the decision is therefore not based on concrete tangible evidence, witness statements, physical evidence etc. as it would be in a regular court case, but mainly on the assessment of the applicant’s personal credibility and the risk he/she is facing in the country of origin. Therefore, the outcome depends to a large extent on the perceptions of the people involved in the procedure: the interviewer, the interpreter, the decisionmaker.

On the surface the Danish procedure is comparatively well functioning. Several extensive interviews are conducted, and if the first instance decision is negative, the applicant will be offered an experienced, independent lawyer for free to represent her/him at the second instance. However, in reality the procedural safeguards are extremely weak in asylum cases compared to other areas of the Danish legal system. The second instance decision is not independent, though Danish politicians often praise it as such. In 2016 the Refugee Appeals Board was reduced in expertise and size. Currently, it has three instead of the former five members and consists of a judge, a neutral lawyer, and a third member representing the Ministry of Integration, which is also in charge of the Immigration Service, the same entity making the first instance decisions. The members that were excluded were appointed by the Danish Refugee Council (DRC) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, representing the expert knowledge on asylum law and the situation in countries of origin. The second instance decision is final and can’t be appealed further.

In addition, direct political pressure and attempts to influence first instance decisions are common in Denmark. A recent example was a direct request from the Minister for Immigration and Integration to the Immigration Service to start a rapid investigation into the cases of all Syrian asylum seekers from Damascus to explore options to revoke their protection status in Denmark, based on the allegedly improved security situation in the Syrian capital. A capital under control of a regime that is not recognised by Danish authorities and whose human rights violations are notorious and well documented.

Further, there is no education or quality control for the interpreters, and training and education for caseworkers as well as judges is inadequate. At the same time, the starting point of the interviews is the assumption that the task is about exposing potential lies or inconsistencies in the story as described by the asylum seekers rather than ensuring a full and thorough understanding of their situation. Torture examinations are too few and are carried out too late in the process. The outcome becomes biased and arbitrary – depending heavily on the personal opinions, experiences and knowledge (or lack of knowledge) of the persons involved in assessing the case – often relying on general profiling rather than individual assessment of the person seeking asylum.

A former caseworker in the Immigration Service’s asylum department is quoted in the report for stating: “It’s not a secret that with Immigration you don’t get points for granting permissions, you get points for giving rejections. That’s how it is. And if you want a divergence, you can find one that fits the occasion. You can rephrase the summary, so it looks like it should be a rejection – within the limits of the law. You are free to do that. I’m not saying that people do that, but they can.”

This basic approach was confirmed by a number of former caseworkers, refugees, lawyers, interpreters, legal experts and NGOs interviewed for the report. Their quotes reveal serious weaknesses in the credibility assessment of asylum seekers in Denmark and confirms my own experience during 14 years working for refugee rights in Denmark.

The report contains ten recommendations on how to improve the assessments. Among them are redesigning the procedures of filing and interviewing, and improving the educating of caseworkers and interpreters. An interpreter with many years of experience in asylum cases said: “80% of the new caseworkers did not know where Iraq was on a map when they started their jobs. They are young, they are full of prejudice, to them the whole Middle East is the same. They go on a few courses, but nothing much. Lucky that they can search the internet during the interviews, haha!”

Over the years I have been involved in hundreds of asylum cases, sometimes following asylum seekers from the moment of arrival in Denmark through the procedure. I am well aware of the complexity of the assessments. I am not suggesting that there is an easy and universal way of establishing whether a person is telling the truth or not. There is always an element of doubt. But as I have illustrated in my report, the current situation leaves the asylum seeker desperately trying to avoid stepping on landmines laid out more or less deliberately by the Danish state. That needs to change.

For further information:

Michala Bendixen/Refugees Welcome, Well-founded fear – credibility and risk assessment in Danish asylum cases, 2020

ECRE publishes op-eds by commentators with relevant experience and expertise in the field who want to contribute to the debate on refugee rights in Europe. The views expressed are those of the author and does not necessarily reflect ECRE positions.

This article appeared in the ECRE Weekly Bulletin . You can subscribe to the Weekly Bulletin here</