Interview with Omar N Cham, PhD candidate at the Vrije Universiteit Brussels. His research focuses on the politics of return migration in his home country, The Gambia.

Can you give us a brief overview of political developments in The Gambia and its history of migration?

The Gambia is the smallest country in mainland Africa with approximately 1.9 inhabitants. The Gambia has a very youthful population with about 60 per cent under the age of 24. In 2016 we had the first democratic transfer of power since independence from Britain in 1965, when a coalition of seven opposition parties surprisingly won against the incumbent president, Yaya Jammeh. Like most countries in Africa, The Gambia has a very long history of international migration. Post-independence emigration from the Gambia was largely attributed to educational and socio-economic reasons. Moreover, after the coup in 1994, many educated and highly skilled people additionally fled the country for political reasons. Also, with the increased use of irregular routes to Europe, many unskilled Gambians took the Mediterranean route to Spain via the Canary Islands to look for opportunities in Europe. In 2015, Gambians were among the nationalities with the highest number of arrivals and asylum claims in Italy and also in Germany – this is very significant considering the size of the population.

What does you research focus on?

My PhD focuses on the politics of return migration in The Gambia. I am interested in examining how cooperation on forced return changed with transition to democracy in 2016. In the previous regime of Yaya Jammeh, there was almost no cooperation with the EU, UK or US on forced return, that is taking people back who are on a deportation order from another country, often after their asylum claim has been rejected. The president legitimated his non-cooperation with the EU along the lines of ‘post-colonial resistance frame “We are not going to be colonized again”, “They have stolen our resources and we have to get back what we rightfully own” “People have the right to migrate and move freely”. The relationship to the EU was not at its best and the EU representative was expelled from the Gambia in 2015. However, with the change in 2016, we have observed an open-door policy towards the West, especially the EU. So, we want to see whether the changes have any impact on cooperation on forced return with the EU, and if so, why.

How did the relations with the EU and return politics change after the regime change in 2016 and how does it affect Gambians with aspirations to migrate?

With the regime change the EU became very active in The Gambia. It supported the new government and provided some much-needed aid through budgetary support, also through the EU Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF) to ‘stem irregular migration’. As far as return is concerned, we have observed quite a number of returnees from Europe, Libya and Niger. Returns from the latter countries are carried out by the International Organisation of Migration (IOM) through its ‘Assisted Voluntary Return and Re-integration’ (AVRR). The effectiveness of IOM re-integration programs is quite contested. Many of the returnees are faced with numerous challenges after their return. A significant number of them are traumatized, frustrated, and often encounter a lot of discrimination. Moreover, the stress of losing valuable assets and having to pay loans previously taking for the journey further makes their situation worse off compared to their situation before migrating. As far as migration aspirations are concerned, I would want to believe that many young Gambians still want to migrate to other countries whenever the opportunity arises. My research will further provide more evidence-based answers in the coming years.

What is the role of NGO’s and civil society in the politics of returns?

Gambian NGO’s and civil society were predominantly dormant as far as the whole discourse on forced return is concerned. Now they are co-opted through funding incentives from the IOM to promote return and keep people from engaging in ‘irregular’ forms of migration. It is important to note that within the whole discourse on “stemming irregular migration” no progress whatsoever has been made on creating legal pathways, even if this is mentioned in the official agenda. The government is promoting returns on several levels, particularly targeting the skilled Gambian diaspora asking them to come back and develop the country. I must say that they have a difficult job in convincing a nation on the dangers of ‘irregular’ migration were 22% of GDP comes from remittances. In the context of established democratic regimes in Ghana and Senegal for example, some civil society organisations and NGO’s have done a considerable amount of advocacy countering cooperation on forced returns. Moreover, personalities also play a role here because the new Gambian president, Adama Barrow, is himself a forced returnee from Germany and presents himself as a positive example for those forcibly returned. So, the change is relatively new, and it will be interesting to see how CSO’s and NGO’s role evolve in the coming years as far as forced return is concerned.

What are the prospects for the future and how does your research play into this?

With the topic of returns and migration becoming increasingly politicised, it will be interesting to see how the growing salience of migration and forced return translate in the next elections results. Later this year I intend to go back home to do some fieldwork and really try to grasp the whole issue around the debate on migration cooperation between the Gambia and EU. With my research I hope to contribute to an emerging and much-needed discourse that offers a non-Eurocentric view of migration cooperation.

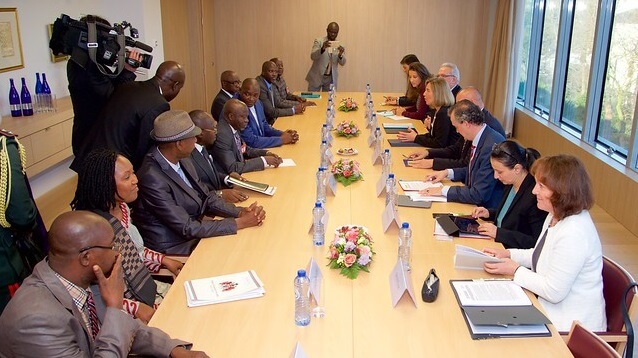

Photo: (CC) European External Action Service, March 2017

This article appeared in the ECRE Weekly Bulletin . You can subscribe to the Weekly Bulletin here.