In the summer of 2018, Jojo Schulmeister returned from the Greek island of Lesvos to showcase a series of photos he had taken with refugees on the Island, in an exhibition called “Laughing Scars”. The Swiss photographer hopes to tell a story of the people that he met on Lesvos in a way that is often missing from the mainstream.

Can you tell us more about you first experiences of Lesvos and why you were motivated to continue going back?

The first time I went to Lesvos was in 2016. I had previously been working in a commercial, but was in the early stages of the pursuit of my interest in photography. I had of course been following the coverage of what the mainstream media had been determining to be a refugee ‘crisis’, but I was one of the many people that was first really galvanised by the now iconic photo of the Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi lying lifeless on a Turkish beach. The image haunted me.

I initially tried to get involved by donating clothes to a Swiss NGO, but when the opportunity came to join them on their mission to the warehouse that they were helping to supply on Lesvos I took it, because I believed it was important to understand what the situation was like for the people that were actually living there. It was hard to know if you could ever trust the images that was created by the media. So, the first time I decided to go it was because I was curious to learn.

But when you’ve seen what is happening there- what people are living through- it is almost impossible to come back and carry on as before – it changes you somehow. I felt that I had to go back to Lesvos, but I only wanted to do so if I could have some sort of purpose or direction there. That’s when I started to consider how I might be able to contribute through photography, and how I might be able to find a different way to tell the stories of the people trapped in this situation.

People are used to seeing pictures of refugees, whether on boats, in tents, on beaches. We end up with a sort of compassion fatigue. The images will make us sad but we will forget as soon as something of our own reality distracts us. The image might even make us stop and say “what can I do?” but when we are not directly confronted by what we’re seeing, the question becomes fairly abstract; unanswered, it too is sure to fade. This notorious image of Alan Kurdi was so shocking that it motivated a lot of people, but if you want to sustain that motivation then what do you have to do? Photograph something more shocking? More shocking than a lifeless 2 year- old? Could that be possible? Did I want it to be? I needed to find a more nuanced way to reach people.

I believe that you can motivate people to engage with this situation if you really make them interested in individuals with identities and stories, in a way that streams of distressing photos can’t, and so this was the project that I set out to design.

Your photo exhibition asked the question “Are we conditioned to see images of people who have fled in a certain way?” Can you give us your answer to this question?

I think mainstream imagery conditions us to see refugees in particular ways. They might be victimised, portrayed as passive, sad, grateful, in need of help. It’s a problematic way to portray people, especially because we can have a tendency to presume this help can only come from the sympathetic European. We can fall into the trap of valorising the volunteer. It’s something we should challenge ourselves on constantly, and I had to be very careful that by entering people’s lives in this way I wasn’t suggesting that I too was some kind of European saviour. The alternative is that refugees are represented as a threatening, destructive force, here to challenge us; change us.

How is your photography different from this mainstream?

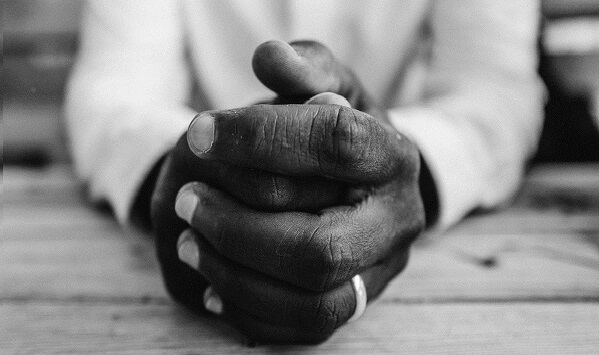

The mainstream media relies on photographing people amidst hopeless conditions. When I was talking to people that might want to be featured in my exhibition I found that they were often willing to have their photograph taken, but not in this degrading environment which they found so disempowering. I chose to respect this by focusing my photography on 3 intimate details; hands, a smile, and a scar. They are intriguing features that can draw an observer in and impart on them a certain closeness, but at the same time the photos maintain a distance- there are no faces, no eyes, no living environment. They create a desire to know more about the person that they are confronted by because they are details that entail a story. The photographs were also accompanied by a book composed of the short answers I had asked each participant to give me- what makes the subject smile? Where did their scar come from? Again the book provides insight but importantly inspires curiosity. Artistically this juxtaposition of intimacy and distance is appealing, but what I wanted to encourage was for people to see the exhibition and leave with the need to know more. If everyone who attended decided to go home and find out more about the situation themselves- by seeking information rather just absorbing the mainstream news- then I would consider this a success.

Why did you focus on young men in your work?

There are thousands of young men in Moria camp; often their stays are lengthy because they are the group considered least vulnerable and most ‘threatening’. I felt like it was important to tell a story about these young men in a way that contrasted otherwise demonising rhetoric. More than this, I wanted to share conversations with each of the participants, to establish connections and reflect something personal. In this setting it could have made some people very uncomfortable were I to try initiate the same conversations in private settings with women or to ask about bodily scars, which would defeat my intention and leave me imposing on people through my photography.

Can you tell us about the audience’s reaction to your exhibition?

We had a real mix of people attend; the curators- Alessa Widmer and Carla Peca – who I am really grateful to, had backgrounds in art history so we had an artistic audience, we also had an activist and volunteer audience, we had people who had read about the exhibition in the press and were interested in the topic, we had people who had walked past it by chance, we had journalists, and perhaps most exciting- we had teenagers- including a group of young people with refugee backgrounds themselves and a group for a local high school, whose teacher has encouraged them all to write about their responses to the exhibition- something I am really looking forward to reading. The rap artist S.O.S performed at the exhibition, which drew in so many teenagers that some of them were obliged to stand outside and watch through the window. A lot of these young people came early to explore the photographs before the performance, and it was really special to see them respond to the images so well, while hearing from speakers who were taking action to make a change to the situation they were seeing in Europe.

I hope that these photos have encouraged people to re-humanise people that have fled persecution in their own perception. I hope our audience will be inspired that they themselves can play an active role in speaking out against these injustices.

Photo: (CC) Laughing Scares, Jojo Schulmeister

This article appeared in the ECRE Weekly Bulletin . You can subscribe to the Weekly Bulletin here.