The EU is considering establishing status agreements with African countries to enable Frontex (the EU border and coast guard agency) to support border management and deploy liaison officers. Commissioner for Home Affairs Ylva Johansson has floated the idea of a political management board for the agency. Switzerland says it would be forced to leave Schengen in the case of a “no” vote in upcoming referendum on Frontex funding. The agency is also under scrutiny in Belgium, where a parliamentary hearing will feature NGO testimony on the role of Frontex in pushbacks.

Ahead of the EU-African Union (AU) summit on 17-18 February, the EU is making plans to expand the role of Frontex in third countries. The Council of the EU is discussing “the swift conclusion of working arrangements including provisions on operational cooperation in the field of return, readmission and reintegration with African countries and deployment of EU return liaison officers (EURLO) to reinforce cooperation with national authorities”. These agreements would follow a model determined in December that sets out a framework for operational cooperation between Frontex and third countries. Internal planning documents say the Frontex teams deployed could be tasked with operational “border management tasks in African countries in order to prevent dangerous departures”. Frontex working agreements, currently in place with 18 countries, have been criticised for serving narrow EU interests – whilst maintaining a superficial pretence of “partnership” – and for lacking oversight. Josephine Liebl, head of advocacy at ECRE, notes that: “at a time when Frontex is in the spotlight for fundamental rights violations in Europe and at borders, and accountability mechanisms appear inadequate, there are risks attached to the agency’s expansion in third countries”. The European Commission will spend 4.35 billion euro of its 2021-27 foreign aid budget on African migration issues, and may also draw on the “migration and border management” budget for external spending “as appropriate”.

Speaking at a press conference following the informal JHA council on 4 February, Commissioner Johansson alluded to a potential bolstering of “political governance and oversight” of Frontex. “We should at least once a year have a political management board for Frontex with ministers,” said the Commissioner. Given Johansson has previously pointed to a lack of Commission control over the agency – and last year proposed a working group on governance, fundamental rights and operations to advise the Frontex Management Board – commentators perceived this as a push for greater accountability. In her most recent comments however, the Commissioner said a board would provide “political steering” and “make policies for the development of Frontex”, without explicitly mentioning its role in sanctioning or investigating rights violations. The current body tasked with monitoring the agency, the Frontex Management Board, is made up of national police authorities and two Commission representatives. More than a dozen inquiries into Frontex accountability for rights abuses have been commenced or concluded in the past year, generating calls for greater oversight of the rapidly-expanding agency. Most recently, the EU Ombudsman said Frontex needed to “ensure a more proactive approach to transparency”. In a report released this January, the EU rights watchdog told the agency to make its operational plans more transparent and improve monitoring of forced returns.

In Switzerland, 62,000 citizens have signed a petition to trigger a referendum on plans to increase the country’s contribution to the Frontex budget. Last autumn, Swiss politicians agreed to boost public funding for Frontex to 61 million CHF annually in 2027, up from 24 million last year. Soon after, campaigners called for a public vote on the question. The No Frontex delivered the petition to the Federal Chancellery on 20 January, chanting “Brick by brick, wall by wall, make the fortress Europe fall!”. The signatures are still being validated by the Swiss government: however, given the required threshold of 50,000 signatures was surpassed, the question will almost certainly be put to the Swiss public in mid-May. The Swiss minister responsible for justice and home affairs, Karin Keller-Sutter, told European interior ministers that the vote would affect Switzerland’s membership of the Schengen Area. “If there is a no to Frontex, it is clear that we will have to leave the Schengen-Dublin area”, said Keller-Sutter. The Schengen Agreement, signed in 1985, requires all members to contribute to the organisations that maintain the internal border-free zone. Nonetheless, in the instance of a vote against Frontex, Switzerland and the other Schengen member states will have 90 days to find a common solution, potentially preventing a Swiss “Schexit”.

Belgium’s federal parliament will hold a hearing on 22 February concerning Frontex involvement in pushbacks. The hearing is an opportunity for civil society actors, including Amnesty International, Refugee Support Aegean, the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) and the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Migrant Rights, to provide testimony. They hope the scrutiny will motivate Belgium to reconsider its increasing financial support to and collaboration with Frontex.

As the EU’s best-funded agency, Frontex also faces allegations of excessive spending. Last year, it was revealed that the agency spent 94,000 euro on a dinner in Warsaw: this month, a 8,500 euro private jet journey was brought to light by media. The agency paid to send executive director Fabrice Leggeri on a chartered flight to Brussels, saying scheduling conflicts had prevented him from flying commercial. When contacted by EU Observer however, LOT Polish Airlines said seats remained available on the flights in question.

For further information:

- ECRE, Frontex: MEPs Freeze Part of the Budget of the Agency Under Scrutiny and Facing Legal Action, October 2021

- ECRE, Frontex: Open Scrutiny Season for Scandal-ridden Border Agency, June 2021

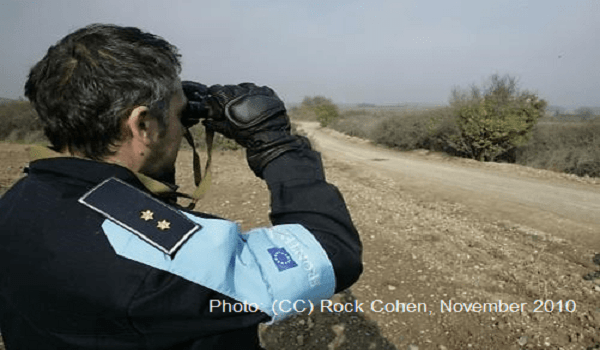

Photo: (CC) Rock Cohen, November 2010

This article appeared in the ECRE Weekly Bulletin. You can subscribe to the Weekly Bulletin here.