Along with other NGOs, ECRE has today published a statement on the proposed Asylum and Migration Pact, under development at EU level.

As civil society is often accused of being too critical and only seeing the negative side of policies on asylum and migration, ECRE has tried to keep a positive outlook on the proposed Pact. Over six months, we have argued that it is an opportunity for the EU to put in place a new strategy and we have proposed concrete ideas for what to include.

Point one is a functioning asylum system in Europe, supported by addressing the implementation gaps that have been identified through detailed analysis of what’s going wrong. Other points on safe and legal routes for asylum and other migration, and inclusion through rights, respect and regularisation, proposed by the NGO statement, might make it into the Pact.

That said, as draft elements from the Pact circulate, it becomes harder and harder to maintain a positive line; and the experience of the last three years hardly generated trust. The presentation of priorities by officials in DG Home in 2019 indicated no change in direction and Member States continue to present non-papers full of restrictive measures.

But new political leaders have assumed their role; they are consulting and deserve a chance, especially as some of the key players in the outgoing Commission were willing to concede that they had “gone too far”. Too many people have visited the Greek islands to really claim that the EU’s approach is an unqualified success. And even without seeing it, we know enough of what’s happening in Libya.

Nonetheless, the NGO statement leads with a warning about the risks of a plans for a (near) mandatory border procedure, with a legislative proposal along these lines apparently at the heart of the Pact. Similarly, return and buying third country support seem to be front and centre. You can’t beat the classics. Some documents in circulation even refer without irony to the success of the EU-Turkey Deal in improving reception conditions in Turkey.

While the 2016 package attempted to restrict access to asylum in Europe through a codification of the EU-Turkey deal model, with the inadmissibility procedure combined with safe third country and first country of arrival concepts, the 2020 variant, possibly to be contained in a “migration management regulation,” is based on a different procedural “solution”. Capturing all or as many people as possible in a border procedure, presumably shortened and without adequate procedural safeguards in place. As argued in the NGO statement, an expanded or mandatory border procedure will lead to increased use of detention. Although there is a new twist on the procedural side, the end result could still look like the Greek islands.

Who arrives irregularly?

There is a risk of confusion of manner of arrival and merits of the case. Models using border detention and rapid return tend to be based on the premise that all those crossing borders are “undeserving” economic migrants, people without a protection claim. Generally, and historically, this is not true. Often it is refugees who have to cross borders to reach protection. There is no justification in any case for sub-standard procedures, but false assumptions about people crossing borders doesn’t help. During the EU’s crisis of 2015/2016 the vast majority of those crossing borders to seek protection were refugees and that was the case in the 1990s; that will be the case again when repression and conflict persist in the EU’s neighbourhood. Policy-makers point to low recognition rates for the people crossing borders irregularly in recent years, around 140,000 in 2019. Yes, recognition rates have fallen, along with arrivals, but that’s partly because refugees are trapped in Turkey (or Syria) or elsewhere en route.

But then, the point of international refugee law and, for now at least, EU asylum law is to have fair and robust asylum processes, with individual assessment, to identify the people being persecuted, regardless of the overall “recognition rates” of the country of origin.

It should also be noted that the recognition rate referred to is invariably based on first instance decision-making and confuses merits and inadmissibility decisions, meaning it is inaccurately low.

Borders are a state of mind

In some of the ideas Member States are pitching, the border procedure will apply to everyone, even if they are not at the border. For instance, someone arriving from a visa-free country or applying for asylum or “apprehended” anywhere on the territory would then be transported to the border or to the border procedure, an idea with a very Hungarian flavour.

An alternative to a procedural change may be a lighter screening, and here the devil is in the detail: it is impossible to comment on the idea of screening, without knowing its purpose, procedure and the implications for persons concerned of the decisions it generates. Clear legal challenges arise if it goes in the direction of a pre-procedure, using nationality-based assumptions to channel people towards particular processes.

What is the problem?

The push for these ideas comes from a disproportionate focus on “secondary” movement, one of the factors that damaged and probably doomed the 2016 package. But onward movement stems from a complex range of factors and would be best addressed by tackling the implementation gaps that exist, such as appalling reception conditions or the asylum lottery in decision-making. Too much focus on onward movement gives the impression of a Commission influenced by certain Member States rather than others.

The NGO statement speculates on the deals that might be done to “buy off the borders” – offers of “solidarity” in exchange for adopting a border procedure. But all of this remains a very bad deal for countries at the EU border. Particularly when the necessary meaningful reform of Dublin, the system for allocation of responsibility, is fast evaporating.

Creating extra procedures, and new physical and legal structures in asylum systems already overstretched, won’t get things moving – instead, simply invest adequate resources in the regular procedure and ensure the procedural guarantees are respected, which increases efficiency as well as fairness.

The unfairness of Dublin is a reason for non-compliance as it creates a perverse incentive to keep reception standards so low that people don’t want to stay and even so low that it becomes illegal to transfer them back. Right now, onward movement is generated by the rapid dismantling of the reception system in Italy and the near removal of humanitarian protection status; trends in litigation show courts judging the situation to be so bad that people cannot be returned.

NGOs have argued for temporary solidarity measures for humanitarian reasons and a rights-based approach to implementation of Dublin III should happen in any case, however ultimately a deeper reform is needed and requested.

During the last reform, the southern Member States worked together in an informal alliance of the Southern Seven, with a common interest in resisting the increase in responsibility that 2016 entailed for them. The dynamics have changed and some may be bought off. Bulgaria and Croatia will be offered Schengen membership. The new Greek government will certainly be more pliant. For Italy and Spain, though, it is harder to see the deal.

All these countries have to ask themselves whether the offer will be worth it if these legal changes oblige them to manage detention centres, establish judicial infrastructure at the borders and juggle the complexity of multiple procedures. Will a few relocation places, a few unwanted case workers who don’t speak the language, or border guards from another country be worth it, to be the site of these new hotspots/controlled centres/detention centres/immigration prisons?

It is not just South, any country with a long external border should object to these proposals (Finland, Poland). The ludicrousness of expecting the Schiphol airport procedure to work effectively at long, geographically complex external borders is a flaw in the plan.

Kafka’s toolbox: buying the East

Whereas conflicts are likely to remain on the border procedure, for the opponents of compulsory solidarity last time round, there may be more to persuade them. Plans under discussion now involve a complex toolbox of “solidarity” options, which will allow countries to show solidarity without ever hosting an asylum-seeker or refugee, and while continuing to flagrantly disregard EU and international law. Diplomatic or operational support would count, presumably the less than helpful deployment of experts to EASO operations (see ECRE’s research), the deployment of border guards (with dogs?). In some plans, returning people will also be solidarity. Yes, rather than agreeing to a fair reform of Dublin, Member States can fly in people who arrive in Europe and send them to Afghanistan to show their solidarity – way to respect Article 80.

Indeed, some Member State officials have excitedly reported that Orban might be on board this time round! Hardly a surprise as this looks like his model, one in which paying for a barbed wire fence or sending a guard with a dog will be considered a solidarity measure.

The others

NGOs have argued that the focus should be on Europe, amidst the fear that the plan will be a continuation of externalisation – the outsourcing of responsibilities and people. If so, it would be predicated on the cooperation of other countries – and this is where it starts to fall apart. Return rates are low because of third countries. It is not due to a lack of prioritisation of return: it is hard to imagine how any more resources could be allocated to deportation. It has been number one priority for 15 years. Everything has been tried. People absconding is also not the issue; increasing detention won’t mean more returns it just means, uh, more detention.

Deportations are simply not welcomed in countries of origin and protests are spreading. Countries are also asking for more in exchange. It is particularly neo-colonial to suppose that a little bit of development assistance can buy cooperation. It hasn’t worked anywhere, with the arguable exception of Niger, the second poorest country in the world where the people affected by its cooperation are primarily not its nationals. Turkey’s cooperation is nothing to do with the money (see ECRE’s analysis); Bangladesh the latest success story was co-opted through the threat of visas restrictions.

Getting wise to Europe’s panic, countries are asking for other forms of benefit before agreeing to return – such as regularisation. The ultimate taboo for Europe.

There are people arriving in Europe seeking work in an irregular way. One reason is the ever-declining options for legal migration through work visas compared to previous decades. Then, the lack of opportunities in countries of origin, poverty, corruption and conflict (some of it generated by Europe). Migration policy will have no impact at all on their decision or desire to come to seek work. Thus, legal channels and mobility should be prioritised instead of return and repatriation. Leaving external policies to do their real job – meeting development, security, trade objectives – would be the best way to tackle displacement.

All about access and resources

Until legislation is presented, it’s hard to say how the proposals compare with the 2016 package. Unfortunately, any change to the legal framework in the current political context is likely to reduce rights, and probably exacerbate inefficiency, irregularity and dysfunction, given some of the myths driving reform processes. Notwithstanding the improvements to the 2016 proposals reflected in the European Parliament’s positions, it was hard to see anything being agreed that added value. A Pact based on making asylum work would be welcome but making the European asylum system function by preventing people from accessing it, is like making the health system work by preventing sick people from going to hospital.

An alternative approach would leave alone the legal framework and focus on addressing implementation gaps. Otherwise there is a risk that EU law is used to resolve internal political conflicts by creating a hostile environment for millions of people in situations of precarity, insecurity and persecution. Not quite what the Treaties intended. A way forward based on compliance with EU and international law, a functioning asylum system through addressing implementation gaps, with EU resources directed towards it, a massive expansion of safe and legal channels, and inclusion through rights, could still be presented.

Editorial: Catherine Woollard, Director of the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE)

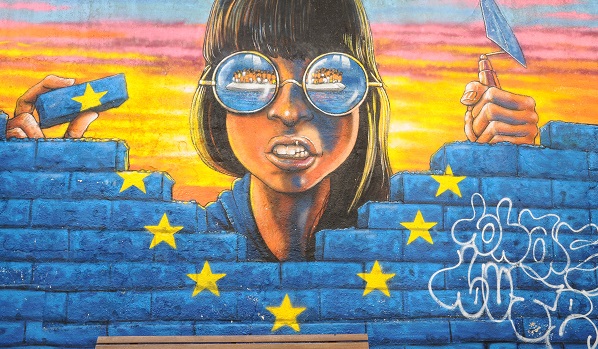

Photo: (CC) David Sutterlütti, October 2016

This article appeared in the ECRE Weekly Bulletin . You can subscribe to the Weekly Bulletin here.