The updated AIDA Country Report on Türkiye provides a detailed overview on legislative and practice-related developments in asylum procedures, reception conditions, detention of asylum seekers and content of international protection in 2021, as well as over the temporary protection procedure and content of temporary protection.

2021 was a year of two halves for the country. The first half of 2021 was not significantly different from 2020, especially considering that the effects of the pandemic were still being felt for what concerned access to the asylum system. From August however – as a consequence of the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan – the high number of people fleeing from the country and reaching Türkiye became the main priority for both the government and the general public. There was a public outcry against the irregular crossings at the Iranian border; access to and from the territory remained deadly with pushbacks continuing on the Greek-Turkish border and ‘blockings’ on the Turkish-Iranian border.

While IOM’s assisted voluntary returns to Afghanistan were halted after August 2021, the Presidency of Migration Management founded its own voluntary returns mechanism. The mechanism is less transparent than IOM’s, and the actual number of returnees is unknown. After being stopped in August as a consequence of Kabul’s fall, returns under this mechanism were resumed at the start of 2022. An upsurge in voluntary returns to Syria was also registered, including to Idlib region where the Turkish government is building houses and investing in schools and hospitals. The voluntary nature many reported returns has been put under question, particularly taking into account various elements that may influence the returnees’ choice, such as the increasingly hostile attitude towards refugees registered in the country, poor conditions in removal centres and the introduction of a new policy of “deactivation” of registration as international protection applicants for people outside of satellite cities.

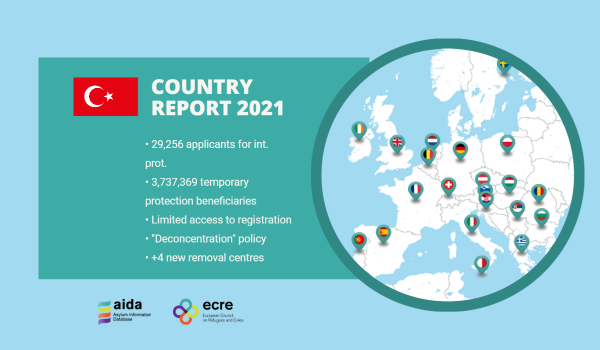

Access to registration remained in fact one of the biggest issues for people seeking international protection in Türkiye in 2021, in particular for Afghans seeking protection. Difficulties in applying for temporary protection were also reported. By May 2022, the lack of access to registration was made official through the so-called “deconcentration” policy, that established that in main cities, including İstanbul, Ankara and cities on the coast, no more than 25% of the inhabitants could be foreign citizens. As a consequence of this policy, 781 neighbourhoods in different provinces are now closed to foreign nationals seeking address registrations for temporary protection, international protection, and residence permits. The lack of registration opportunities affected access to basic services for prospective applicants, and forced them to live in an irregular migratory situation.

One of the most prominent shortcomings of Türkiye’s legal framework for asylum remained the failure to commit to providing state-funded accommodation to asylum applicants. This resulted in important issues of homelessness or sub-standard living conditions putting them at serious risk of discrimination and serious violations. Refugees’ material conditions further considerably worsened due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-2021 and the economic crisis of 2021.

Integration programmes were not widely discussed in 2021, possibly due to the challenges faced by the national economy. The EU continued to provide funding including for education services and cash assistance programmes. In the context of the implementation of the EU-Türkiye deal, readmissions to Türkiye were frozen throughout 2021. As of June 2022, 33,961 Syrians had been resettled (since 2016) to the EU under the 1:1 scheme.